Some athletes are just born with it.

Their speed, reflexes and stamina are simply on another, mutant level. Their vision and grey matter allow them to see scenarios unfolding that it takes instant replay and a telestrator for others to break down. We admire the gifted for their aptitude. We loathe the gifted because it just comes so damn easy to them.

But not everyone with privileged prowess excels in professional sports. There are equalizers: Work ethic, conditioning, adaptability, intelligence. You anticipate deficiencies in the gifted. Nobody’s perfect.

That is, until you compete against someone like Scott Niedermayer and realize that, yeah, sometimes they are.

Ken Daneyko, one of his defensive partners with the New Jersey Devils, had the realization early in Niedermayer’s career in the NHL. The Devils had lost a few consecutive games. Morale was down, and the coach’s ire was up.

“Coach had implemented a no-puck practice, a skate-until-drop practice. That’s what we had for an hour solid,” recalled Daneyko.

“I came back to the dressing room looking like I had been in the shower. Just dying.”

In walked Scott Niedermayer, having endured the same grueling workout. Daneyko, winded and aching, watched Niedermayer remove his practice jersey, and then his shoulder pads, expecting to see similar evidence of physical exhaustion.

“He had, like, a little raindrop of sweat. That’s it,” recalled Daneyko.

“You just kind of shake you head.”

Former Devils coach Larry Robinson said Niedermayer's conditioning was legendary.

“He was the Eveready battery. Never ran out of energy,” he said.

“I just wish I had his legs for one game. What a player I’d be!” said Daneyko.

“One of the greatest skaters that ever played the game. It was just effortless for him.”

But it wasn’t all effortless.

• • •

It’s easy to believe in the charmed life of Scott Niedermayer, who will enter the Hockey Hall of Fame on Monday along with Chris Chelios, Brendan Shanahan, Fred Shero and Geraldine Heaney.

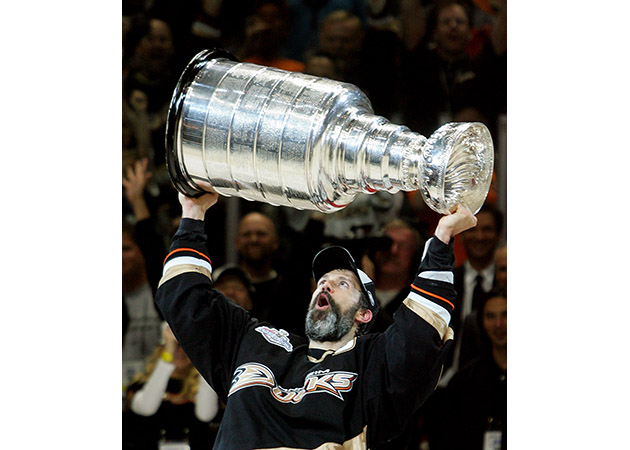

He’s the only player in history to have won the Stanley Cup (four times: 1995, 2000, 2003 with the Devils and then 2007 with the Anaheim Ducks); the Winter Olympic gold medal (2002 and 2010 with Canada); the IIHF world championship (2004); the World Cup of Hockey (2004); and the World Junior title with Canada in 1991. Add in the 2004 Norris Trophy and the 2007 Conn Smythe, and there isn’t much Niedermayer hasn’t won. He was a dynamic two-way defenseman, and a subtly strong leader.

But he didn’t possess those traits when he broke into the league as an 18 year old in 1991, and wouldn’t for several years after that.

[Brendan Shanahan on 'twitch' to play, Hall of Fame memories & his dad Donal]

“He wasn’t one of Jacques Lemaire’s favorites at the start, because he was taking a lot of chances offensively, and Lemaire was the type that wanted his defensemen to play more defense and just be a puck-carrier,” recalled Robinson, the San Jose Sharks associate coach who coached Niedermayer with the Devils for over a decade.

“So that was my job, to make him more of a two-way defenseman.”

Niedermayer was drafted third overall in 1991 by the Devils – they acquired the pick from the Toronto Maple Leafs for Tom Kurvers, whose biggest accomplishments in the NHL were winning a Cup with Montreal in 1986 and being traded for Scott Niedermayer – after a junior career with the Kamloops Blazers of the WHL. He put up remarkable numbers for a defenseman: 82 points in 57 games during the 1990-91 campaign.

But like so many other elite offensive defenseman, he used his blazing speed to cover up for defensive deficiencies.

That’s what Scott Stevens saw when he met Niedermayer: a remarkable young talent that lacked defensive technique. “It’s not something that came naturally to him, but he worked at it,” said Stevens, Hockey Hall of Fame Class of 2007.

“It’s all a learning process. He became a much better all-around defenseman under Jacques.”

And under Robinson, Hockey Hall of Fame Class of 1995 and one of the best defensemen in NHL history.

“I don’t like to change somebody’s style of play. I more or less worked on him on the finer points of stick position and body position,” he said.

“But he was a coach’s dream because he was a great skater. Probably one of the best pure skaters I’ve ever seen. You just had to teach him when to pick his spots.”

But for all the technique Robinson instilled in Niedermayer, his exceptional skating would help make him a dominant defenseman and eventual hockey immortal.

“He could change the whole tempo of a game. He could control the game with his speed,” said Daneyko. “I remember certain games when he would be behind his own goal line, the other guy would be going the other way, and he’d skate the length of the ice to catch him.

“His skating ability … it was like he was floating above the ice.”

[Chris Chelios Q&A: On whether he could still play at 51, his post-NHL life & what the future holds]

Niedermayer would play for the Devils from 1992-2004, posting over 30 points in every non-lockout season and topping 50 points twice. While that’s not exactly Paul Coffey territory, it’s a significant total considering the Devils’ trap-tastic style during most of that run.

Had Niedermayer played on another team, in another system, perhaps his career totals would be north of 24th in points for a defenseman with 740.

Was it ever a point of frustration for him?

“It frustrated him at times. But it was a double-edged sword, and I think he was intelligent enough to understand that, but I think it made him a better hockey player,” said Daneyko.

• • •If there was a flaw in Scott Niedermayer, Scott Stevens would have found it. He played with him on the ice, spent time with him on the road.

But he said the holes in Niedermayer's game weren't evident. Outside of his cultural tastes.

“Working with him was pretty easy. Just move the puck to him and skate things out of trouble. One of the best skating defensemen I’ve seen. He could go forever,” said Stevens.

“Great person. Great talent. But his music wasn’t very good. Heavy Metal. I’m a country guy.”

(Who knew Scott Stevens was a little bit of country, and Scott Niedermayer was a little bit of rock ‘n roll?)

Niedermayer played with two of the best defensemen of his era in Stevens and then Chris Pronger with the Anaheim Ducks. They were also two defensemen who were his antithesis. You can’t picture Niedermayer snarling at the opponents’ bench saying “YOU’RE NEXT!” like Stevens, or sarcastically holding court with the media like Pronger.

Unlike those two born generals, leadership wasn’t always an intangible for Niedermayer.

“He became a leader,” said Daneyko. “He used to be a player that just wanted to go and find his thing, but gradually he became a leader.”

He’d lead by example, and picked his spots for motivation in the dressing room. In that sense, Robinson said Niedermayer reminded him of Hall of Famer Bob Gainey: a man of few words, but ones that resonated when he would speak.

One such moment was in the Ducks’ 2007 Cup victory against the Ottawa Senators, when Daniel Alfredsson fired the puck at Niedermayer in the last seconds of the second period of Game 4, in a startling bit of captain-on-captain violence.

All eyes were on Niedermayer between periods, and he responded with words that managed to both motivate his team and ensure they didn’t snap back with retribution.

“Let’s not get caught up in it. It was pretty simple,” recalled Niedermayer.

He had been with the Ducks for one season when GM Brian Burke made the Pronger trade with the Edmonton Oilers, bringing a Type-A personality into a dressing room that was essentially Niedermayer’s. They’d share the ice and the leadership of the team.

There was a chance it could have been combustible. Instead, they led the Ducks to the first Stanley Cup.

“On the ice, our styles were very different. We never felt like we were stepping on each other’s toes at all. He’d do his thing, on be off doing my thing somewhere else,” recalled Niedermayer of Pronger.

“We really had our own styles. I did what I thought was best to lead with my personality. I can’t remember one time when there was a conflict at all.

“As different as our games were, our personalities were just as different. He wanted to win at all costs, and I benefited from that with a championship.”

The Ducks’ Cup in 2007 was Niedermayer’s fourth, differing from his previous three by the sweater he was wearing and the distinction in his facial features.

“I often kidded him about it. You stay in this game long enough, the gray hairs come out,” said Robinson of Niedermayer’s epic playoff beard. “And wait until you become a coach: That salt and pepper’s going to be mostly salt.”

Niedermayer’s an assistant coach with the Ducks, although he doesn’t travel with the team typically. Robinson believes he has what it takes to become a head coach in the NHL if he chooses that path.

Daneyko believes his former teammate could forego the coaching and still be playing at 40.

“He retired about eight years before he had to,” he said.

Niedermayer hung up the skates in 2010. Now, he’s a first-ballot Hall of Famer. Just another accomplishment, for a player that accomplished nearly everything a player could in hockey.

“I just had the utmost respect for Nieds,” said Daneyko. “It’s no coincidence that no matter where he goes, the team wins.”

|

|

|

Results 1 to 1 of 1

-

11-09-2013, 02:01 PM #1Administrator

- Join Date

- Jun 2007

- Location

- Canada

- Age

- 49

- Posts

- 60,770

- Blog Entries

- 3

- Downloads

- 9

- Uploads

- 12429

The making of Scott Niedermayer, Hockey Hall of Famer

The making of Scott Niedermayer, Hockey Hall of Famer

Similar Threads

-

The making of Scott Niedermayer, Hockey Hall of Famer

By admin in forum Sports NewsReplies: 0Last Post: 11-09-2013, 02:00 PM -

Ed Belfour, ‘flabbergasted’ 1st-ballot Hockey Hall of Famer

By admin in forum Sports NewsReplies: 0Last Post: 06-29-2011, 05:44 AM -

What hat will future hall of famer Corky Miller wear in the Hall?

By Slappy LaRue in forum Predictions and PropheciesReplies: 0Last Post: 10-12-2008, 01:15 AM -

Kimbo Slice a MMA hall of famer?

By Whoda M in forum The CageReplies: 4Last Post: 10-05-2008, 08:05 PM -

Future Hall of Famer

By tony_holmes_316 in forum Predictions and PropheciesReplies: 0Last Post: 08-10-2008, 01:05 AM

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks